Wild Honey Bee Study

Project point of contact: Keith Browne, [email protected]

The National University of Ireland, Galway (NUIG) in collaboration with Native Irish Honey Bee Society and the Federation of Irish Beekeepers Association are studying the wild* honey bees in Ireland to discover the number and distribution of their colonies in order to devise strategies for its conservation. We have some promising preliminary data from a launch of the project in 2015 (see below) and with funding from the Dept. Agriculture, Food and the Marine we are now working with the National Biodiversity Data Centre seeking help from citizen scientists to extend the study and discover what wealth of wild honey bees remain in the Irish landscape.

*Also referred to as feral, free-living or unmanaged

How You Can Help

If you see honey bees living anywhere other than a beehive please let us know by recording the information here:

https://records.biodiversityireland.ie/record/wildhoneybeestudy

We’re aiming to capture both where free-living honeybee colonies currently exist and where they like living. Honey bees typically like nesting in elevated (ca. > 1.5 m or 5 ft high) cavities like hollows in trees, walls and roofs of buildings and can be particularly noticeable when workers are seen frequently flying to and from the nest entrance on warm sunny days. If you find a free-living colony ideally take a photo and note the following:

- Location and date

- How high off the ground it is

- How long has it been there (if known)

- What direction the entrance is facing

- Are the honey bees behaving aggressively

- Has a beekeeper taken a swarm from the colony (if known)

If you find what you suspect to be a honey bee colony at or below ground-level then it is probably not a honey bee colony but that of a bumblebee or wasp. Therefore, it’s important to know how to identify a honey bee.

How to Recognise A…

Honey bees are a relatively small bee compared to many bumble bees and carder bees. From a distance they look much less “furry” although they do have many fine hairs, especially on the thorax. The picture above shows only one type of bumble bee for comparison however there are over 100 other types of bee species. For Ireland, there is only one native honey bee, a sub-species called Apis mellifera mellifera or the Northern dark bee.

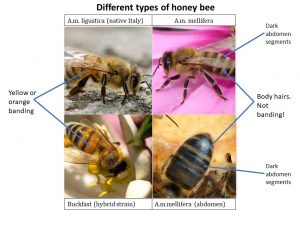

Honey bees tend to be seen on flowering plants including trees but may also be observed taking up water from shallow pools or spills. Their abdomen can range in colour from very dark brown (almost black) to light orange with various shades and colour banding in between such as in the comparison pictures below. We are interested in colonies of all colour morphs.

It is generally considered that the darker honey bee the is the native form, Apis mellifera mellifera. Lighter coloured honey bees tend to be thought of as either a different introduced sub-species such as Apis mellifera ligustica or a hybrid form between the two types. Wasps, like the Common Wasp Vespula vulgaris, can also be confused for honey bees however they have conspicuous yellow and black banding as seen in the picture above.

…Honey Bee Colony

Honey bees are cavity dwellers and their colonies are usually found by observing the activity and noise of a large number of honey bees at a small entrance, particularly on warm sunny days. Colonies are usually seen in elevated positions, in trees, walls and roofs of buildings although entrances have been found in unlikely places such as hollow statues, compost bins, bird boxes and graveyard crypts, so rule nothing out.

Honey bees are cavity dwellers and their colonies are usually found by observing the activity and noise of a large number of honey bees at a small entrance, particularly on warm sunny days. Colonies are usually seen in elevated positions, in trees, walls and roofs of buildings although entrances have been found in unlikely places such as hollow statues, compost bins, bird boxes and graveyard crypts, so rule nothing out.

From a distance, the colony can sometimes be confused with those of wasps, in cases where the wasps are very active. Some bumble bees are also cavity dwellers and will nest in small ground cavities which can also look like honey bee colony entrances however the bees are larger and there is a relative lack of numbers.

Additional Information

Background Information on Honey Bees

Of the 99 species of bee in Ireland there is only one native honey bee species, in fact it’s a sub-species, Apis mellifera mellifera, the dark northern Western honey bee. Moreover, because this sub-species inhabits much of Northern Europe with its wide variation in climate, the honey-bees in Ireland and each individual country or region could be more accurately referred to as ecotypes, with characteristics finely adapted to their specific environment.

Honey bees are included in the pollinators that pollinate wild plants and crops. The importance of the honey bee lies not only in the sheer numbers of potential pollinators, up to 60,000 bees can make up a colony, but also in their management as a semi-domesticated animal. The ability to manage colonies means they can be moved to where they are of greatest use to us as crop pollinators.

The Problems

Wild honey bees are threatened by habitat loss and chemical use in our landscape. Additionally, through hybridisation with introduced forms, sub-species and ecotypes can lose genes and gene complexes adapted to their local environment thereby reducing their fitness. The adaptations of these ecotypes give the colonies the potential to be less stressed than those that are introduced or hybridised. The reduced stress on a colony consequent of being closely adapted to their environment is likely to be a component in the extra fitness required to survive the cumulative stress of disease and infestation, such as with Varroa destructor leading to greater sustainability. Recent international research considers that locally adapted ecotypes of honey bees are the sustainable way forward for the conservation of both free-living and managed honey bees.

Honey bees are treated in the same manner as fully-domesticated livestock with free movement of honey bees permitted throughout Europe in much the same manner as cattle or pigs. However, whereas cattle or pigs, for example, are controlled in their mating habits though artificial insemination and fencing to control distribution, honey bees mate freely between managed and wild populations creating a population better described as semi-domesticated. Where introduced sub-species, such as Apis meliifera ligustica from Italy or hybrid commercialised strains such as Buckfast or Starline, are present there is potential for genetic admixture that can remove the adaptations of the local population to its environment resulting in reduced colony longevity, which in turn makes it less sustainable.

Varroa destructor

To compound the problems outlined above, the introduction of pests such as Varroa destructor through movement of managed colonies has had a devastating effect on the honey bee population, both managed and free-living.

It is an obligate ectoparasite of honey bees originally introduced into the Europe’s Western honey bee population from its original host, the Eastern honey bee Apis cerana, through the legal movement of managed colonies. Varroa was first discovered in Ireland in 1998, allegedly introduced by the movement from the UK into Ireland of a single infected colony.

Varroa feed on the body tissue of both larval and adult bees acting as a vector for many viruses, with the result that weakened colonies usually die within two years of infestation. The result of this infestation has been substantial widespread honey bee colony deaths across Ireland and Europe to the extent that free-living Apis mellifera mellifera is considered party or wholly extinct across much of its natural range.

NUIG Research: The Pilot Project for Free-living Honey Bees

In conjunction with researchers in Limerick Institute of Technology and collaborators in Switzerland and Portugal it has been determined that the Irish honey bee population of both managed and free-living colonies is mainly Apis mellifera mellifera and only partly hybridised with other sub-species. This picture differs considerably from most of Europe where Apis mellifera mellifera is also native and is, for the main part, thought to be either extinct or highly intermixed with other honey bee subspecies.

Following the confirmation of a rare unprotected population of Apis mellifera mellifera in Ireland, attention turned to the state of free-living (wild or feral) honey bee populations. In late 2015 the NUIG launched a pilot project asking citizen scientists everywhere to locate, report and monitor the survival of free-living honey bee colonies across all of Ireland. Over 200 reports of honey bee colonies in buildings, trees, walls and a mixture of other types of cavities were received and we have been able to monitor the survival of some of these.

The study showed that some free-living colonies can survive for 3 years or more without human intervention. It also showed that a high proportion of the free-living population are Apis mellifera mellifera, the sub-species native to Ireland. To fully understand this free-living population and devise strategies to protect it for Ireland and the rest of Europe, NUIG have launched this new appeal funded by the Dept. Agriculture, Food and the Marine in collaboration with the Native Irish Honey Bee Society, the Federation of Irish Beekeepers and the National Biodiversity Data Centre.

Research Papers: