Celebrating native meadows

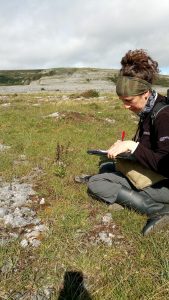

Dr Maria Long, Grassland Ecologist with the National Parks and Wildlife Service, explains why existing semi-natural grasslands are so important.

The extraordinary value of existing semi-natural grasslands

Grasslands are familiar to us all. The best kinds (for nature) are those with a wide variety of grasses and other plants. These are managed by light grazing or mowing, and typically don’t get much, if any, fertiliser. In these habitats, summer is a glorious time – the flowers of the grasses blowing in the wind, in varying shades of green, and with brightly coloured pollen. The dabs of bright colour from the grassland flowers such as clovers, ox-eye daisies, stitchworts, knapweeds, bedstraws, orchids, etc. It’s a real feast for the senses, not just our eyes. The fragrance can be magnificent, and the sound is something to cherish – the rasping of grasshoppers, the buzzing of bees and other insects, and the chirping of birds.

Note that all these elements are significantly weakened or missing in intensive farming situations, where the vast array of species which occur naturally are replaced by one or a small number of planted-in species, typically perennial ryegrass and perhaps white clover. There will be some nutrient-hungry ‘weeds’ too, like thistles and docks, but only a few species. In these situations the dearth of diversity is typically mirrored under the ground too. But of course we need food and agricultural production. So the key is to choose wisely where in our landscape we prioritise maximum production, and where we might prioritise other things, like biodiversity, carbon storage, water management, etc. By taking this approach, we can protect and enhance remaining species-rich and semi-natural grasslands, and all the range of services they provide. And it is certainly not at the cost of food production, as they produce food of course (e.g. milk and meat), and at a very high quality – but it will typically be lower in volume.

Existing semi-natural grasslands and the use of ‘wildflower’ seeds

In a long-standing, old or ancient grassland, a complex web of life has evolved. With each component (be it a fungus underground, or a mite, or a moss above ground, or a particular beetle) – these have all evolved to co-exist, and are all inter-reliant. Compare this with a planted-in agricultural sward of ryegrass, or with a ‘wildflower meadow’ seed mix that you buy in the shop. There is simply no comparison in terms of biodiversity and in terms of value – the pre-existing semi-natural grasslands may look less colourful, but it outshines sown-in mixes in every other aspect. However, there may be value to using ‘wildflower’ mixes in some instances (e.g. in horticulture, in urban settings), but in the wider countryside, they have little relevance, and are poor substitutes for even a modestly diverse naturally-occurring sward. And in fact, their use can be massively detrimental, for example where existing areas of semi-natural habitat are destroyed in order to plant in seed mixes.

But you might think – what harm? Surely these ‘wildflower meadow’ mixes are good for pollinators? The answer is that some flowers are better than none, but that what’s best is native, locally sourced flowers. And what’s more, being ‘good for the bees’ is not the only function that semi-natural grasslands perform. Here are some others:

- Semi-natural grasslands support a huge proportion of our biodiversity – for example, a range of insects need open ground to live and breed, and they in turn are food for many bird species. Most butterflies for example, also many snails, beetles, earthworms, etc. These are key food for many birds and mammals.

- Other key ‘ecosystem services’ (or… ‘things provided’) include:

- Food – for domestic stock, but also a wide range of wild animals, including pollinators. And us too – e.g. mushrooms.

- Shelter – for a wide range of invertebrates and small mammals, also for ground-nesting birds

- Carbon sequestration & storage – e.g. floodplain grasslands capture and store more carbon than peatlands and woodlands!

- Water regulation – semi-natural grasslands help filter water, and also help store it. Plants with different root depths are important for this, as for the carbon storage

- Erosion – a healthy sward with a mix of plant species holds soils in place much better than a reseeded sward of low diversity

- Semi-natural grasslands are a reservoir of wild species diversity, and a potential source of genetic resources, possibly medical also

- Pest control – e.g. ladybirds can thrive in semi-natural grasslands, and in turn eat aphids from our crops; also small birds can thrive in semi-natural grasslands and their hedge, and they then also eat pests from crops

- Agricultural and rural heritage – a huge part of Irish identity is tied into our ‘green’ image, our rural economy and our agricultural heritage, yet most of the Irish population now quite disconnected

- Semi-natural grasslands contribute enormously to our well-being, enjoyment, sense of place and connection to the natural world. Urban dwellers flock to parks to experience green spaces and to de-stress, and those lucky enough to live near open-access semi-natural grasslands, or parks with sensitive meadow management, get huge benefit from simply being in and experiencing the diversity supported in these areas.

Getting from ‘A’ to ‘B’ – restoration

It’s clear that if one wants to move from a species-poor or intensively managed grassland or other habitat, towards are more semi-natural grassland… using the ‘wildflower’ mixes available in most places is not the way to go. The best thing to do is, surprisingly, the ‘do nothing’ approach. But it’s not really do nothing, it’s about reducing or ceasing any nutrient inputs, and then managing sensitively. So in a lawn, it might involve less frequent cutting, and on a farm, it might involve stopping fertiliser application and putting out less stock. In a park or garden, a key change is to mow and remove the cuttings. Whatever the situation, the key is not to keep adding nutrients, but to slowing decrease them over time. This allows more plant species to grow. Conversely – adding nutrients bolsters ever fewer species to survive, with those adapted to taking up nutrients out-competing all the others.

But in some situations, just simply reducing nutrients may not be enough. If a site really does need ‘help’ to become a species-rich grassland (e.g. if the aim is conservation management, rehabilitation or restoration), what options other than shop-bought seed exist? Thankfully there are a few. These techniques are relatively new in Ireland, with only a few people/organisations carrying them out. But that is set to change.

Green hay:

This involves taking a hay cut from a similar site in the locality (known as the donor site), and taking the cut on the same day to the receptor site. The cut vegetation (which is still green – hasn’t yellowed from drying yet) is spread on the receptor site and allowed to dry. Techniques vary in their detail, with some people scarifying the land a little beforehand to ensure some bare soil is exposed. At the least, it’s advisable to cut the existing vegetation very short. Turning the green hay to shake loose as many seeds as possible is recommended. This technique may be carried out on more than one year at a site, but in many cases one is enough to introduce locally-relevant, naturally occurring seed and to increase diversity. It is important that sites are as similar as possible – pH, moisture, elevation, etc. should all be taken into consideration. And they should be close by too, to allow for efficient transport of the material, but more importantly, to ensure that the suite of species transferred is locally relevant and locally evolved.

Green hay being collected in the UK from a species-rich ‘donor’ grassland, for use at a nearby ‘recipient’ site for restoration. Image from ‘Save our Magnificent Meadows’

Brush harvesting:

This technique involves using specially designed equipment to sweep or brush along over vegetation in late summer, the aim being to shake loose and collect seeds. This material can then be used as a seed source. It can be used at a different site, or re-applied at the same site, e.g. after works, for example to re-establish vegetation after windfarm construction. If seed is not to be used immediately, it must be dried carefully and thoroughly. There are some machines available for spreading the seed, but this necessitates cleaning and processing the seeds. If the scale of the operation is not too large, seed can be hand broadcast from the back of a pick-up/trailer or similar.

Options at the garden scale:

The techniques above involve the use of relatively specialised machinery, and a small number of companies and local authorities have purchased these. The techniques are most suitable for larger scale habitat restoration, rather than garden-scale – e.g. restoration of hillside heathland after wind farm construction, but may also be increasingly used by local authorities on land they own.

On the garden scale, people can collect seed from local species by hand, and scatter or plant at home. If doing this, make sure you have permission to collect, and also ensure that there are good populations of any species you collect from. Some species may also be grown from seed at home, and planted in as ‘plug plants’. This works well with species such as common knapweed. The meadow at the National Biodiversity Data Centre is a great example of where this was employed. A small number of young plants were planted into the meadow (previously lawn), and there is now a healthy and spreading population of knapweed, making up a valued part of the new meadow.

Meadow National Biodiversity Data Centre: Year 1 Meadow National Biodiversity Data Centre: Years 4+

The biodiversity meadow at the National Biodiversity Data Centre was created by reduced mowing. It started out very grassy (year 1 image) and gradually become more flower-rich over the coming years. The only species added through local seed collection was Common Knapweed (right). In Year 7, the first orchids were spotted!

Summary

In summary – our existing semi-natural grasslands are sometimes almost invisible, and it is imperative that we value them for all the services they provide. We need food production to be prioritised across much of our land, as is currently the case, but we desperately need to prioritise many of the other benefits that semi-natural grasslands can give us in areas where these survive. We should never use shop-bought ‘wildflower’ seed mixes in natural settings – instead we should use sensitive management to encourage the natural vegetation to emerge and thrive. Where restoration is an aim, techniques such as green hay and brush harvesting have an important and growing role to play, and it will be important to set up and grow a network of donor sites across the country. At a smaller scale, local seed collection by hand, and the judicious use of ‘plug plants’ can also help restore semi-natural grassland. But really…. keeping it simple is best. Put the mower away, and when it is used, lift the cuttings, and nature will do the rest in her own time.

By Dr Maria Long

Maria is the Grassland Ecologist in the National Parks and Wildlife Service

Sometimes scientists and those who work in biodiversity conservation use words or phrases that many people may not be familiar with. If you find a word or phrase you are unfamiliar with, take a look at the wildflower seed pages glossary which provides definitions for some commonly used terms on this part of our website.