Grasslands – our most threatened habitats

You may be surprised to learn that species-rich meadows and grasslands are among the most threatened habitats in Ireland, with huge losses happening almost unnoticed. For example, surveys undertaken by the National Parks & Wildlife Service in the past 15 years, and just six years apart, have shown losses of approximately 30% in area of our best quality calcareous grasslands, and in species-rich hay meadows too (Martin et al., 2018). This is staggering, and it’s worth taking a moment to let that fact sink in.

This is made all the more stark when you think that hay meadows, in particular, would have been one of the most common grassland types in Ireland just a short few decades ago (up to at least the end of the 1970s). The main drivers of loss are related to agricultural changes, with both intensification of land use and land abandonment being the top issues. Land-use change to forestry is quickly becoming another key cause of losses too though.

Lowland hay meadow, with abundance of common flowers and grasses. Sadly, this is an exceedingly rare habitat in Ireland now.

But there are grasslands everywhere you might say! Ireland is famous for its grasslands, and its green image! … … Well yes, it’s true that huge areas of our country are under grasslands, much more than most other countries in Europe as it happens. But what may not be so obvious at first glance, is that there are many different types of grasslands, and some are much more valuable for nature, and for a range of ecosystem services (e.g., flood management, carbon capture, etc.), than others. Another way of looking at it is that some grasslands are now used solely to produce food, without taking into account the other functions, or the degradation of soil, water and other aspects. An ideal is a balance – food production and being good for nature!

‘Improved’ or semi-natural

To look in a bit more detail, at one end of the spectrum we have agriculturally ‘improved’ fields – those which have been ploughed and re-seeded with fast-growing grasses, and in these grasslands, chemical inputs are high. Fertiliser will be used to encourage grass growth, and other chemicals may be used to keep pests and weeds at bay. These fields are dominated by a small number of plant species – those planted in by the farmer (e.g., perennial rye-grass, perhaps clovers), and a handful of nutrient-hungry ‘agricultural weeds’ (e.g., docks, thistles, nettles) who can tough it out in such environments. There is little space for most elements of nature in many of these grasslands, and their biodiversity value is not high, their soils are likely to be depleted, and their ability to function all round is impaired. Food production value is likely to be high, however.

Improved grassland, with low biodiversity value, in the midlands of Ireland.

At the other end of the spectrum, semi-natural grasslands are those which have not been ploughed or re-seeded, and which don’t receive large amounts of chemical inputs. But absolutely crucially, they are still managed. Here, there will be a wide range of plant species, sometimes an incredible diversity… all having arrived of their own accord over decades, or even longer, and all jostling for space and a share of the things they need (e.g., light, nutrients, water, etc.). These grasslands support a wealth of natural life and biodiversity, with many insects and invertebrates living in amongst the diverse sward, as well as in the healthy soils. As a knock-on consequence, there will be a varied set of birds and mammals to be found, feeding on these invertebrates. These are managed habitats, but the management is relatively low-intensity, and is in tune, more or less, with nature. Food production will be lower, but all round, the grasslands will function better – e.g., healthier soils, more water and carbon capture, etc.

The reality is that vast areas of grasslands in Ireland fall somewhere in the middle of this spectrum. We would do well to shuffle as many of our grasslands towards the lower-intensity management end as we can, while still maintaining food production, but not prioritising it ‘at all costs’ on so much of our land.

So what’s the issue? Can’t we just protect the remaining valuable species-rich meadows and grasslands, or create new grasslands?

One issue in the challenge of grassland conservation is that good quality semi-natural grasslands are not always obvious. Clearly anyone can see an oak wood, and tell that it’s valuable, and there would be outcry if someone started to chop it down. But how many people can tell a ‘good’ semi-natural grassland from one that’s poor in biodiversity? It’s a bit more subtle. And how many people notice or care if a farmer ploughs a field and re-seeds it? It’s so commonplace that few would bat an eyelid. But if it was a species-rich semi-natural grassland, which had existed for tens or hundreds of years, then it is no less tragic a loss than someone felling a woodland.

And similarly, it is just as difficult to try to re-create an ancient grassland, as it is an ancient woodland. The interactions that have evolved both above and below the ground between the myriad of inhabitants in a long-established grassland cannot be recreated overnight and cannot be designed by man. So, just like when you plant new oak trees, you know it will take 100s of years for a diverse oak wood to develop, and so too, the same is true for grassland communities.

What can you do? (And what’s it better not to do!)

Given the rapid loss of species-rich meadows and grasslands in the wider countryside, how we manage the areas near our homes is becoming more and more important. Your lawn is a grassland, as is the strip of grass outside your housing estate, and there are many more examples besides. These are all mini-meadows, and if managed appropriately, can play an important role in helping the survival of our grassland plants and animals.

The key message is that encouraging native plants to flourish is the BEST option for pollinators, and indeed all biodiversity. We need to come to love the beauty in the ordinary! And so the best plan is to support the species which are naturally occurring, and not to plant in other seeds, whether that’s grasses (e.g. re-seeding your lawn) or ‘wildflower’ mixes. Native species are the ones which are adapted to be there, and importantly, those are the species that pollinators and other wild animals want – not showy plants from a packet, or bulked-up horticulturally-bred varieties.

Wildflowers in area of amenity grassland which is being managed sensitively – e.g. infrequent mowing, removal of cuttings, no ‘weed’ control chemicals. Within this small managed grassland in a housing estate in Portlaoise, the very rare green-winged orchid appeared in 2020. This shows that even unassuming areas can support surprising diversity.

Risks of wildflower seeds

You might wonder if I’m being a bit negative about wildflower seeds? I don’t think so, but I’m also keen to acknowledge that everyone who buys and sows wildflower seeds believe that they are doing a good thing. And so therefore it even more important to point out the potential risks. And there are a few.

From the conservation point of view, there are a number of risks. These mixes often contain non-native plants, often in contradiction to what the packet says! Sometimes the seeds of species which are native here are sourced from abroad, meaning that they are not adapted to local conditions. One which I find particularly poignant is that in the UK, they are now struggling to undertake meaningful surveys of some of the rarest plants, because it is becoming increasingly difficult to tell the native populations from the newly introduced ones. And so some native species may slip into extinction, being obscured by their counterparts which have been seeded-in from elsewhere.

Even if this scenario doesn’t unfold, newly introduced plants will have a different genetic make-up to the already occurring ones, and if interbreeding occurs (as is likely), loss of genetic quality occurs. As an example, I’m worried that the suspiciously large, tall and bulky cowslips which are growing along some of our major roadways as a result of added seeds, will interbreed and compromise our native populations of cowslips, which have adapted to conditions here over 1,000s of years. These may seem like common plants to be worrying about – but cowslips are so rare in Northern Ireland that they are protected by law, and recent surveys by the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland (BSBI) suggest that cowslips are increasingly rare as meadow species, though they are holding on along roadsides (read article here, pg. 55-77). But for how long can we be confident that we are seeing a ‘real’ Irish cowslip, not one grown from seed originating elsewhere?

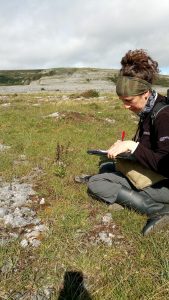

Native cowslip in the Burren, Co. Clare.

As well as conservation concerns, there is also a risk to agriculture. Recently Glanbia has stopped selling wildflower seeds until a system is in place to check and vet the seeds (currently there is none). This came about because ‘black-grass’ seed was found in seed mixes for sale in shops when Teagasc grew some seed to check. This grass is a close relative of some of our native species, but it is a real problem. It is a weed of arable crops and is resistant to herbicide, meaning that if it gets established on an arable farm, it can put that farmer out of business. It is a very serious matter, and a risk that Glanbia and others were simply not willing to take.

So remember, most seed mixes you can buy in the shops are not from Ireland, in spite of the wording on the packets. And even if the seeds are, then they may be from a different part of Ireland or may be a horticulturally-bred variety of that species. Remember… local is always better, and best of all is letting the naturally occurring species of grasses and flowers flourish.

Take-home messages for managing mini-meadows:

If you manage any area of grassland, no matter how small, here are some key things to remember:

- Mow/cut/strim/scythe less often

- Remove all cuttings

- Learn to love our common wild flowers – clovers, buttercups, dandelions, thistles, nettles, etc are all very valuable for wildlife

- Learn to love the naturally occurring grasses too – these are very valuable to our native pollinators and other bugs and beasts. Meadows are supposed to be mostly green!

- Allow for some diversity in management – i.e. let some areas go unmanaged (e.g. in corners), let some areas grow tall, and keep other areas shorter… this means that lots of creatures might find their niche

- Collect seed from nearby if you like – down the road or in a nearby field perhaps. Collect in autumn, and sow then, or in spring. Set into pots initially, or into the ground, either will do, but make sure to make some bare soil if you are sowing directly into your lawn.

- And finally, buying ‘wildflower’ seeds can seem like a great idea, but it is nearly always better to refrain. Many are not what we think they are, and actually pose a threat to our precious semi-natural grasslands! If you really must, then check and double-check the provenance and choose only locally sourced native species, and prioritise common species of flowers and grasses in your mix. A quick tip is to avoid anything with blue or showy flowers!

By Dr Maria Long

Maria is the Grassland Ecologist in the National Parks and Wildlife Service

Sources cited:

Martin, J.R., O’Neill, F.H. & Daly, O.H. (2018) The monitoring and assessment of three EU Habitats Directive Annex I grassland habitats. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 102. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, Ireland.

Long, M.P., Breen, C., Conaghan, J., Denyer, J., Faulkner, J., MacGowan, F., McCorry, M., Northridge, R. and O’Meara, P. (2017) Telling the story of eight uncommon/ declining Irish plant species – first results from the Irish Species Project (ISP). Irish Botanical News 27, 55-77.

Glanbia and black-grass concerns in wildflower seed:

https://www.farmersjournal.ie/glanbia-suspends-sale-of-some-wildflower-seeds-625975