Our wild bees are in trouble, but in their droves, people are taking actions to help. We can never adequately express our thanks for the support and goodwill shown by all sectors for the All-Ireland Pollinator Plan. One of the main actions the Plan promotes is to cut grass less often. The trailblazers took to this straight away – they’re the people who don’t care what anyone thinks. To the rest, even if it’s understood how valuable an action it is, deciding to let your lawn grow can make us mildly uncomfortable.

There are hurdles to overcome – parents who offer to cut your grass when they visit (regardless of your age or theirs); neighbours who tell you that what you’re doing is so important but you can see they would rather chop their arm off than do it themselves; people who ring local council offices to complain about ‘lazy staff’ and that it’s a disgrace that public areas aren’t being mown.

The truth is that we’ve somehow fallen into a pattern of managing our private and public grass like golf greens. To humans, a neatly manicured lawn looks tidy, but without being dramatic, to our wildlife it must look a bit like the apocalypse. It would be like us returning to a desolate earth with almost all our food crops wiped out. To change this, we have to move away from what we’ve become accustomed to. That is always hard. Longer grass is no different – it can jar a little until you get used to it.

“To humans, a neatly manicured lawn looks tidy,

but without being dramatic,

to our wildlife it must look a bit like the apocalypse.”

|

|

Pollinators need more areas of native flower-rich grassland – no matter how small – in order to find enough food.

Why is the Pollinator Plan obsessed with letting grass grow?

I think if our wild bees could talk, the two things they would ask us to do is to let our hedgerows flower and to let more grassy meadows bloom. If we did this across the island it would provide a range of native wildflowers throughout the life cycle of our wild bees and other insects. Hedgerows flower in early spring and meadows from late spring into late summer. This means not cutting hedgerows so often and not cutting grass so often – actions that save us time, effort and probably money. It’s also what the science tells us will work – native plants in hedgerows and meadows are very rich in the pollen and nectar that our insects need to survive. Wild bees don’t make honey, so they have no way of storing food. They are never more than a few days away from starvation so it’s very important that there is a continual supply of flowers in the landscape to feed on. We can’t expect them to be there only when we need them to pollinate our apples, soft fruit or oilseed rape.

In Mayo, longer grass on roadside verges, in field margins on farms, or small meadow in gardens might just save the endangered Great Yellow Bumblebee from extinction. Along our main transport routes, it might be pollinator-friendly corridors that allow movement within the landscape and that give pollinators a fighting chance against climate change. For the rest of us, in our parks, gardens, schools, businesses or farms, it might not be so dramatic, but if you take action – even in a small urban garden – you can be sure that what you are doing is helping.

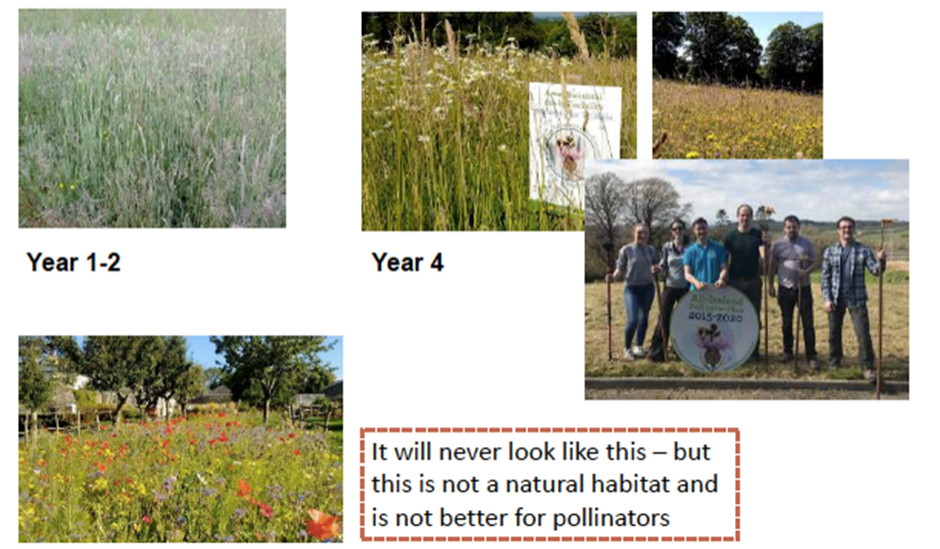

Why isn’t my meadow awash with colour?

Many of us have an unrealistic picture-postcard expectation of what a ‘wildflower meadow’ should look like. Bees see colours differently to us and they don’t much care if meadows look pretty. A perfect meadow for bees is one that has grass mixed with plenty of pollen and nectar-rich flowers. It is the hay meadows of old that they like, rather than the jam-packed blues, reds and yellows that you see on wildflower seed packets.

While there is huge interest in creating meadows like this, this is not necessary for pollinators, is not natural, and is costly and difficult to achieve in the long term. (Photo by Richard Croft, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wiki-commons)

The huge advantage of allowing meadows to regenerate naturally is that you don’t have to purchase or plant seed – our native wildflowers will grow when you give them a chance. They’re often there in the soil – popping their little heads up each year in expectation – only to have them chopped off when the mower comes out every few weeks.

When you reduce mowing, you can decide to have a long-flowering meadow or a short-flowering one. Either can be done from the smallest patch to the largest field. Some of the best areas I’ve seen have a mix of long and short-flowering meadows as well as regularly mown grass – all in the one location.

- Long-flowering meadows are cut once a year in September and the cut grass is taken away. They provide both food and shelter for insects.

- Short-flowering meadows are cut throughout the year, but less frequently than you’re normally used to, so that more flowers get a chance to grow and provide food amongst the grass. The grass is removed each time rather than mulching back in.

Some areas will be stunning as soon as you stop or reduce mowing. This year I’ve visited sites that have been full of wildflowers, including bee orchids, in the first year the mowing regime was changed! It is very important to point out that this is unusual. It depends on the fertility of your soil to start. Very fertile soils don’t support wildflowers because fast-growing grasses and weeds take advantage of the nutrients and grow quickly, at the expense of slower-growing wildflowers. Removing the cuts of grass will reduce fertility over time and this gradually provides better conditions for flowers to establish.

You have to be patient – long-flowering meadows improve year upon year if you manage them correctly

Most of us will have to go through several stages with our garden patches, strips of lawn or meadows of long-flowering grass. If it’s very grassy and has pernicious weeds (thistles, nettles, docks) it indicates high soil fertility. This happens on farmland that has had a lot of fertiliser application or run-off. It also happens on lawns and amenity areas due to the grass being regularly mowed and cuttings not being removed (returning nutrients to the soil as the cut grass breaks down). If your meadow is at this stage, you need to remove those weeds throughout the year; take away the hay cut each September and be patient. This is where many of us can get a bit uncomfortable with the new regime – it won’t look good to humans (or to bees) for several years.

If it’s on Local Authority land, these long-flowering meadows can be a very hard sell, particularly if it’s in a very public area. You can put up signage and persevere, but you could also cut your losses and try somewhere else where the soil might be more immediately suitable. You could also choose a location that’s less public to more gradually introduce the idea of natural meadows to the wider community.

|

|

|

Bird’s-foot-trefoil (left), Dandelions (centre) or Clover (right) might not be what you’re aiming for when you plan your ‘wildflower meadow’ but all of these wildflowers offer lots of pollen and nectar for pollinating insects.

The next stage your long-flowering meadow will reach – and many will be lucky enough to start here – is that you’ll have plants like sweet vernal grass, red clover and meadow buttercup. These are known to play a key role in the development of flower-rich grasslands as they interact with soil fungi and provide better conditions for other flower species to establish. If you’re here, you are well on your way! If you continue managing your meadow to remove the cut each September, it should become more flower-rich year upon year. How wildflower-rich you’ll be able to go depends on your soil and location. Really good meadows might have 15-20 different plant species per square meter. These are the kinds of wildflowers you’re after – Knapweed, Dog Daisy, Red Clover, Field Scabious, White Clover, Dandelion, Yarrow, Devil’s-bit Scabious, Hawkbits, Vetches, Selfheal, Meadow Vetchling, Yellow-rattle and Bird’s-foot-trefoil. It’s still not the front of a wildflower seed packet – that’ll never happen, is not natural and isn’t better for pollinators!

Knapweed – not to be mistaken with Thistle – offers pollinators a rich food supply.

Advice:

- In long-flowering areas, cut around the outside and if it’s large, cut paths through the centre of the meadow so that people know it’s deliberate, they can walk through the meadow, and it still looks managed.

- Put up a sign so that visitors understand what you’re doing.

- Long-flowering meadows can’t just be left and ignored. You will still need to remove things like Thistles, Nettles, Docks, Hogweed and Ragwort in the first few years. Once it establishes this should no longer be necessary. If you leave these pernicious weeds – they’ll be back next year, probably in greater numbers.

- If the grass growth is very strong and the vegetation is falling over under its own weight, cut sooner, e.g. July and again in September. After a few years as soil fertility is lowered, this earlier cut will no longer be necessary and one cut at the end of the summer will be enough.

- Don’t have long-flowering meadows in unsuitable areas. We would never advocate taking out areas where children play, or people walk – it’s about managing landscapes that work for people and wildlife.

- If it’s on public land, choose carefully where to let grass grow to develop a meadow area. Very fertile areas will take a while to become flower-rich and may be a hard sell to the public. Also try to avoid planning a long-flowering meadow in areas where it might become a litter trap. Many public meadows do have to be walked for litter before the autumn cut so that machinery isn’t damaged.

- When you cut your long-flowering meadow in September, if you can, let the grass lie for a few days to allow more seeds to drop. Don’t worry if this isn’t possible though, as it may be easier to cut and bale in one action.

- If you’re opting for reduced mowing – it’s fine to play it by ear on your cutting regime – if your meadow contains flowers and bees are using them, leave it for as long as you are comfortable with or for as long as your mower can still manage to cut and lift. If there are no flowers – it’s fine to cut.

- There is no evidence that meadows attract rodents.

- Think in advance about how you are going to manage long-flowering meadows – the hay cut needs to be removed in autumn. This does involve work!

|

|

- If you see your Local Authority has taken steps to reduce grass cutting, contact them (or your local representative) to express your support. Sometimes the people who don’t like something can be more vocal and end up with a disproportionate voice.

- If you started a meadow area, and you really don’t like it; your co-workers have disowned you; or your partner is about to divorce you – scrap it and do something else. At least you tried! The Pollinator Plan recommends lots of different actions so that there is something for everyone!

Challenges:

- The biggest challenge with meadows is removing the cut in September. For large meadows you might have the right machinery, or you might have an arrangement with a local farmer who can bale and remove for you. We have two small long-flowering meadows at the National Biodiversity Data Centre and each September we have it cut with a normal mower and then the staff spend a few hours raking and lifting it off. It is hard work but it’s also a bit of a social occasion and it’s been extremely rewarding to see how the meadows have become more flower-rich each year just because of this raking.

Our meadows at the National Biodiversity Data Centre in Waterford have taken a number of years to regenerate and develop but with patience, the flowers have returned and in greater numbers every year.

- Rather than bemoan the difficulty of managing meadows, volunteers in the East Cork Biodiversity Networking Programme (ECBNP) have shown inspirational leadership and found funding to buy the right equipment and have already created extensive meadows in their local area. Some Local Authorities have also been investing in new machinery and we will need to see more of this in the future if we are to bring meadows back to our public spaces.

- Another difficulty is what to do with all the long grass that we’re not used to collecting – particularly on public land. In smaller private sites it can be composted but otherwise this is a huge challenge. The Don’t Mow Let it Grow campaign in Northern Ireland works with local farmers who are happy to cut and bale parkland grass and road verges and take away as fodder. Where this isn’t possible, I can only hope that there are innovative people out there who might spot an opportunity – perhaps some of it can be centrally collected and sold as forage; perhaps it can lead to more public composting facilities and sold/supplied back locally; or perhaps there are other innovations out there to be identified e.g, Lincolnshire County Council in the UK are currently exploring using grass verge cuttings as biofuel.

- Another challenge on public land is with contractors who have done the same thing for many years and are unsure of how to change or perhaps don’t have the equipment to manage areas in a new way. These are all challenges to be faced.

I just can’t tolerate the look of my meadow anymore!

If you have a long-flowering meadow, this is a perfectly normal reaction come mid-August! It will look dead and is untidy to even the most ardent fan by now. If you can, it’s best to tolerate it until September to give the wildflower seeds a chance to drop. If you do, you’ll reap the rewards the following year.

Should I not just plant wildflower seed?

No, it’s much more sustainable and cost effective to let meadows regenerate naturally. It also means that what grows is suited to the conditions and is meant to be there. The All-Ireland Pollinator Plan does not advocate the use of seed bombs to recreate meadows. This is difficult to write because I know that people are buying seed bombs with the best of intentions, believing they are doing the right thing. We are very aware that it can look like we’re telling people we need ‘to plant’ more wildflowers but no, what our pollinators need most are the native wildflowers already under your soil to be let grow and flower! Often seed bombs might contain species that are native to Ireland, but are not made from seed collected from Irish plants. They are also an inefficient way to plant seed.

A better option if you are determined to add seed is to collect a small amount locally from pollinator-friendly wildflowers in the area and use this in your meadow. See our guide for advice on this: https://pollinators.ie/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/How-to-guide-Seeds-2018-WEB.pdf

Packets of bought wildflower seed can be dominated by things like blue Cornflowers. Cornflower isn’t a native plant to Ireland. It provides some nectar and a little bit of pollen, but it is a small fraction of what you’ll find in native plants like Dandelions or Knapweed or Oxeye Daisy, which are incredibly rich in both (and free). If you do want an immediate splash of colour in a small area you could also consider horticultural alternatives e.g., planting fast growing seeds like Phacelia (green manure) or bulk sunflowers planting if you have a sunny site.

Thanks to all who have embraced this action

Less mowing means more native wildflowers which means more bees. More native wildflowers also mean a healthier, more colourful, more distinctive and more attractive place for us to live and for others to visit. Having an island that cherishes its meadows and its hedgerows would be a fantastic legacy to leave to future generations.

“Less mowing means more native wildflowers which means more bees”

Reducing mowing in order to help pollinators does work. Evidence from the UK shows that naturally regenerated field margins supported over 2.5 times the abundance of flowers and 3-16 times the abundance of bees! It works, but within the Pollinator Plan we do want to acknowledge that it is not easy. Next year, we hope to produce a second guideline document to provide more practical advice on managing these meadows once you have them and to share the knowledge that’s been built up over the last number of years across the island.

Meadows are increasing across Ireland. It’s the uncomfortable people who are sticking their necks out who deserve most credit. For me, the real heroes in the Republic of Ireland are in the Tidy Towns groups volunteering their time in small towns, villages and cities in every county. Countless Tidy Towns groups have embraced this action to reduce grass-cutting since the Pollinator Plan was published in 2015. These are the people who have had to sell this new idea to their communities, but who have persevered, despite all the challenges, and are normalising it for everyone.

My favourite phone call of the year so far was a lady who rang with a problem. Somewhat reluctantly they had agreed to (slightly) reduce their grass cutting regime in three local areas. Their problem was that now there were so many bumblebees feeding on wildflowers within the grass that they couldn’t cut it without running over all the bees!

If those bees could talk, they would definitely say ‘THANK YOU’!

Dr Úna Fitzpatrick is co-founder and Project Coordinator of the All-Ireland Pollinator Plan and is a Senior Ecologist with the National Biodiversity Data Centre.