All-Ireland Pollinator Plan co-founder and Project Coordinator, Dr Úna FitzPatrick explains how she welcomes the wild bees that visit her garden

Bee on Lavender, a pollen-rich choice for your garden. (© Andrea McDonagh)

Having bumblebees visit my garden improves my health. They pollinate the vegetables and fruit I grow, but it’s much more than that. There is a tranquility to sitting on a summer’s evening watching bumblebees flitting from flower to flower, collecting pollen to bring back to feed their young. I think many of us know it instinctively, but more and more scientific studies are now showing that spending time in nature is good for us, both physically and mentally.

I have a small urban garden geared towards two boys and the sports they play. Having bumblebees come to visit doesn’t need a ‘wild’ garden, nor does it need a large garden or much effort. Containers on the patio or a window box will do it.

Queen bumblebees emerge from hibernation in the spring when the temperature begins to rise. For me, it’s a true sign that winter is finally over. Most of those queens have spent the winter burrowed underground, often in north-facing slopes to avoid the winter sun – in case they think it is spring too soon. They avoid freezing to death by producing glycerol, which acts as antifreeze, and prevents the water in their bodies from turning into ice crystals.

Bees are our most important insect pollinator because they visit flowers to collect pollen to feed to their young, as well as feeding exclusively on the nectar of flowers as adults. Their entire life-cycle is dependent on interactions with flowering plants.

The queen’s first task, on emerging from hibernation, is to find a nest site and then to collect pollen to feed the first batch of young. Almost all of the 21 different types of bumblebees we have in Ireland make their nest on the surface of the ground or just underneath. Undisturbed long grass or the longer grass at the base of a hedgerow are perfect sites.

Nature is amazingly interconnected, and here it’s the pollen the queen collects that will stimulate her ovaries to begin producing eggs. She’ll lay those eggs in small batches on the ball of pollen she has collected. Bumblebees don’t produce honey like honeybees, but close by, she’ll have created a tiny little wax pot and filled it with nectar. This allows the queen to lie on the eggs to keep them warm (like birds) and feed at the same time. Bumblebee eggs need to be kept at around 30˚C for about four days. Brooding her eggs is hard, energy-burning work and she needs to visit large numbers of flowers each day to feed. During each foraging trip, the brood will cool down, so it’s vital that her nest is located close to rewarding flowers.

‘my ten-year-old son is probably brainwashed,

but he pointed out that dandelions

provide food for bees in spring,

let children tell the time in summer,

and then provide seeds for birds in autumn’

Bumblebees don’t nest in my small garden unfortunately, but they do visit to find food and I try to make sure I have something to help them out early in spring, which is their most difficult time of year. The buff-tailed bumblebee is always our first visitor and will visit to feed on the Crocuses, my one small Willow tree (Salix aegyptiaca) and Berberis darwinii, a bright orange shrub that is choc-a-bloc with pollen and nectar. Immediately after those, the most important flowers on the menu are to be found on another small yellow shrub called Broom, the herb Rosemary and my beloved Dandelions.

I try to let as many Dandelions as possible grow in the lawn up until mid-April. I spend a lot of time promoting Dandelions, but it’s hard to stress just how important they are to bees in spring. I know my ten-year-old son is probably brainwashed, but he pointed out that Dandelions provide food for bees in spring; let children tell the time in summer; and then provide seeds for birds in autumn. Truth be told, having Dandelions in the garden doesn’t come naturally to everyone in our household – especially the one who usually controls the lawnmower! It was only the number of goldfinches visiting to feed on the seeds that finally sold the idea!

Úna’s garden balances her boys’ playing areas and room for wildlife. Assigning a strip of your lawn for wildlife brings great rewards for human health as well as biodiversity.

By May and June, most bumblebee colonies are in full-steam-ahead mode. The queen is laying eggs which develop into female workers and those workers spend their days out gathering pollen to bring back to feed the next set of larvae in the nest. Nectar-rich flowers provide them with the energy they need to do this. Believe it or not, the most important thing in my garden at this time of year is the small unmown areas of the grass where clover and bird’s-foot-trefoil grow naturally and provide food.

By now, bumblebees are also very busy feeding on (and pollinating) my currants, early raspberries and small apple tree.

Bumblebee on clover, an important food plant in summer © Leon Van Der Noll

Through the summer into autumn, I try to have a mix of pollinator-friendly perennials and herbs that will sequentially flower so there are no hunger gaps through the seasons. The key things I’ve planted are: Thyme, Lavender, Oregano, Catmint, Cala-mint, Wallflower, Comfrey, Verbena and Salvia. I also have a Laburnum tree that will be buzzing in June. The lovely thing is that by summer we’ll be reaping the reward of our bumblebee visitors with the strawberries, raspberries, currants, apples, courgettes, tomatoes, peas and pumpkin, all safely pollinated by my visiting bees, and ripening nicely.

By mid-late summer, it’s time for the bumblebee males to appear. The males take no part in child-rearing or looking after the nest. For male bumblebees, life is all about drinking (nectar) and chasing girls. Joking aside, it’s not an easy life, as with bumblebees it’s most definitely the females who are in charge! Once old enough, males are ejected from the nest to fend for themselves. Those bedraggled bumblebees you see hanging onto flowers in mid-late summer are males who have nowhere else to spend the night. In our garden it’s the Lavender that is their favourite hangout. Also, at this time of year, the old queen will allow some of the female workers to become new queens who leave the nest to find mates. In late summer and early autumn, I make sure there are still some flowers in our garden so that new bumblebee queens can fatten up before going into hibernation. If they don’t reach a healthy pre-hibernation weight they won’t survive through the Irish winter. The things we’ve planted are Aster novi-belgii, Rudbeckia and flowering Ivy. With bumblebees, only the mated new queen survives to hibernate over the winter.

In our garden, the last bumblebee to hang around is the ginger, common carder bee. Come early October, they’ll have all but disappeared again. I like watching that natural rhythm and I like the sense of renewal that spring brings.

We also have solitary bees in our garden. You probably do, too, but have just never noticed them. They are an amazing, charismatic gang of 77 different species in Ireland. A whole new set of characters to watch out for – leaf cutters, wool carders, white-faced bees, sweat bees, mason bees and more. They, too, are disappearing due to hunger because our countryside offers less wildflowers today, making gardens all the more important as refuges in an increasingly sterile landscape.

Gardens can be vital pit-stops for our pollinators, birds and other wildlife. It doesn’t cost much, and you can be guaranteed that what you are doing is really helping. I don’t spend all my time sitting in my garden thinking about bees. However, I do love that when you pause for a minute in a pollinator-friendly garden – there they are, calmly going about their business as they have done for millions of years. I would hate if we didn’t protect that for future generations.

One can’t overstate the value of Dandelions to our bees (© Donna Rainey)

Dr Una FitzPatrick is a Senior Ecologist with the National Biodiversity Data Centre

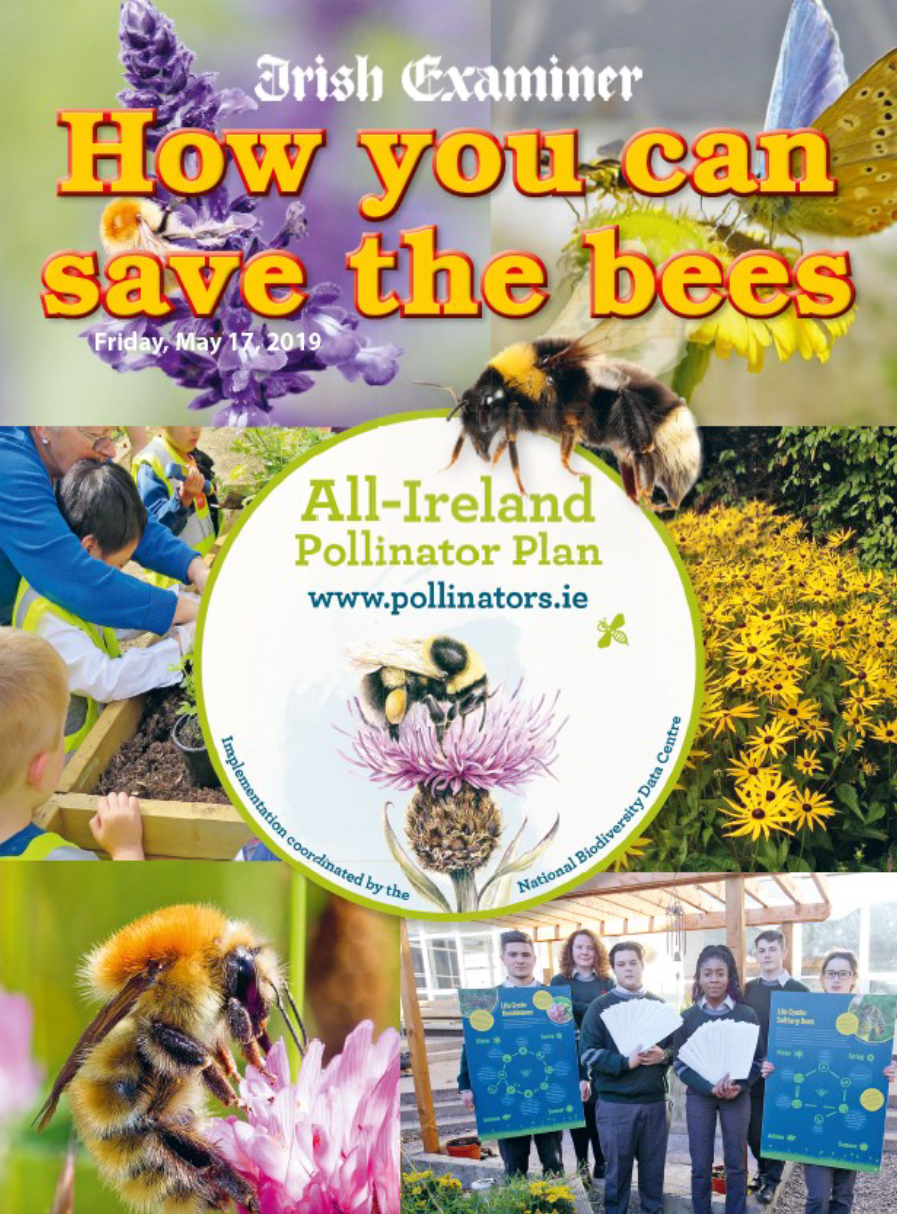

This article was first published by the Irish Examiner in their booklet to mark World Bee Day 2019: How you can save the bees: